This paper was written by Neil Jacobs and published as part of Open Access Week 2018. It can also be downloaded as a PDF document.

Introduction

This paper outlines the current state of the organisational, cultural and technical landscape related to OA repositories in the UK, trends and recent developments, and suggestions for improvement.

Background

OA repositories as we know them arose from the Santa Fe convention 1999 [1], whose recommendations in February 2000 included the specification for the technical protocol (OAI-PMH [2]) that enables their contents to be harvested and aggregated. In the UK, the following decade was characterised by Jisc support [3] for universities to establish and enhance a network of institutional repositories, the development of some UK and global support services, as well as by the birth of UK (later Europe) PubMed Central, led by the Wellcome Trust. At the same time, there was increasing interest among research funders in OA, with some Research Council policies supporting the use of repositories from 2006. The Finch Report downplayed the use of repositories for OA, but the subsequent announcement by HEFCE of their use in the next REF reinforced their role. Most recently, the role of repositories in OA is being discussed in the context of Plan S [4], and its description of repositories as supporting editorial innovation and archiving.

Repositories in the UK today

According to the global directory OpenDOAR [5], there are 258 repositories in the UK, of which 180 hold research articles and, of these, 160 are institutionally-based (as opposed to being departmental or disciplinary). According to the Universities UK 2017 Monitoring report[6], some 48% of articles with a UK author were openly available online other than on the publisher site, of which 15% were in institutional repositories, 13% in subject repositories, and 50% (likely illegally) on ResearchGate. The submission of items into institutional repositories is often mediated (or at least checked) by library staff, whereas that into subject repositories is usually direct by the author. While the REF policy has prompted many universities to increase the investment in their repositories, for others staffing for repository support remains rather low.

The Research England / Research Councils / Jisc / Wellcome report “Monitoring sector progress towards compliance with funder open access policies” [7] gives a more detailed view of how repositories are being used to implement OA policies. For example, it notes that 35 per cent of HEIs only use an institutional repository for research management, with a further three per cent only using a current research information system (CRIS). The majority of institutions (58 per cent) use both.

Software

Of the 160 institutional repositories, 27 use the DSpace open source software, 98 use the EPrints open source software, and 13 use Elsevier’s PURE product. A sizeable minority of those using open source software in fact pay for a hosted solution managed by a third party. Those with local installations are often running rather old software, perhaps because an accretion of local configurations makes it difficult to upgrade.

Technical standards

Beyond OAI-PMH (see above), both HEFCE and the Research Councils were deeply involved with Jisc in the creation of the RIOXX [8] metadata schema for repositories to share information in a standard way that included most/all of the information needed to demonstrate compliance with their policies. RIOXX also includes information needed to demonstrate compliance with the H2020 [9] policy.

There is a consensus that existing repositories are technically now rather dated. A set of recommendations for a next generation of repositories [10] has been released by an international working group [11]. Some repository platforms are beginning to implement these.

Services and tools

ORCID [12] has broad take-up in the UK, with 91 universities now members of the UK ORCID consortium [13]. Most have implemented active two-way synchronisation with the ORCID API, enabling them to confirm on ORCID that researchers are affiliated with that university, and populating university systems (including repositories) from ORCID records, eg on publications. Authors can authorise ORCID to import relevant publication information from Crossref [14] into their ORCID record. The Jisc Publications Router [15] automates notifications to university repositories from Crossref, PubMed and directly from several publishers. This enables repositories more easily to meet the OA eligibility requirements of the REF.

CORE [16] is the largest open aggregation of OA content from repositories and elsewhere in the world. It harvests all UK repositories. It uses RIOXX metadata where possible and pushes records to OpenAIRE to comply with the H2020 OA policy. CORE also provides the potential to open up new research opportunities through text and data mining which have been made possible by the Text and Data Mining copyright exception [17].

Overall landscape

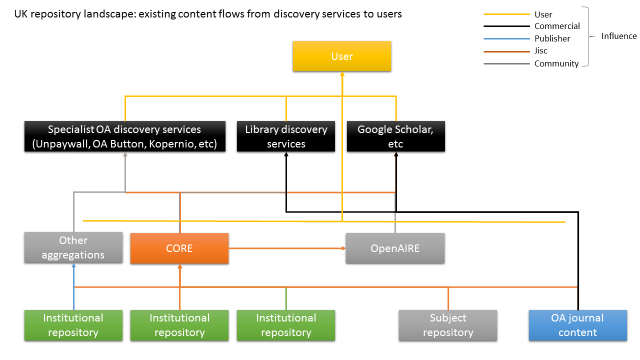

The following diagram illustrates the main features of the repository / OA landscape, from a content provider perspective, and focusing on journal articles and similar objects, rather than on monographs, data or other kinds of research output:

The following diagram illustrates the main features of the repository / OA landscape from a user perspective:

It is clear from both these diagrams that this is a crowded, potentially confusing and inefficient landscape, though one filled with innovation. For example, the question of how discoverable and accessible OA content really is, either from repositories or journals, has led to the development of a range of OA discovery products competing for space and efficacy against established public infrastructure, well-established library discovery services and long-standing commercial services. Arguably though, no one product or service serves as a panacea.

Weaknesses in the UK repository landscape, and possible remedies

| Weakness | Possible remedy |

| Because of the importance of local configurations, many institutional repositories have not been upgraded and are running on out-of-date software. | Cloud hosted solutions are available, and Jisc is developing a shared, multi-tenant open research repository for both data and OA publications. |

| The number of repositories and lack of coordination in what gets deposited in them means their contents are not a coherent or systematic representation of UK research. | Aggregations and discovery services are able to deduplicate. Furthermore, CORE will provide a deduplicated feed to relevant institutional repositories to ensure complete coverage. In the medium term, repositories should get persistent identifiers for their contents. |

| In most cases, research papers in repositories are unclear on the licence terms under which they are made available. | In the UK and elsewhere, copyright exceptions may allow certain kinds of reuse regardless of the licence.

Crossref enables article level licensing to be declared for each version of an output; this should be used more consistently. Publications Router passes licencing information to repositories from publishers, Crossref and elsewhere. Rights retention initiatives such as Plan S and the UK Scholarly Communications Licence [18] may clarify rights. |

| Repositories do not make research outputs available on the web in natively digital ways using modern standards, APIs, etc, making it difficult to find and reuse their contents. | The recommendations from the Confederation of OA Repositories International Next Generation Repositories group are being implemented by many repository platforms, and will be incorporated into the Jisc shared repository. |

[1] http://www.openarchives.org/sfc/sfc_entry.htm

[2] https://www.openarchives.org/pmh/

[3] Including the Repositories Support Project http://www.rsp.ac.uk/

[4] https://www.scienceeurope.org/coalition-s/

[5] http://v2.sherpa.ac.uk/opendoar/

[6] https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/monitoring-transition-open-access-2017.aspx

[7] https://re.ukri.org/documents/2018/research-england-open-access-report-pdf/

[8] http://rioxx.net/

[9] http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/grants_manual/hi/oa_pilot/h2020-hi-oa-pilot-guide_en.pdf

[10] https://www.coar-repositories.org/files/NGR-Final-Formatted-Report-cc.pdf

[11] https://www.coar-repositories.org/activities/advocacy-leadership/working-group-next-generation-repositories/

[12] https://orcid.org/

[13] https://www.jisc.ac.uk/orcid

[14] https://www.crossref.org/

[15] https://pubrouter.jisc.ac.uk/

[16] https://core.ac.uk/

[17] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/375954/Research.pdf

[18] http://ukscl.ac.uk/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.